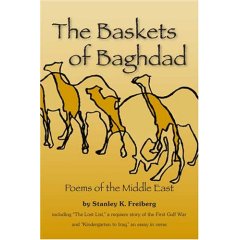

The Baskets of Baghdad

Fifty reprinted poems from the original 1967 text; a musical score of the title poem; Baghdad and Victoria, BC intermingled in a requiem short story; and a historical, cultural, literary essay in poetry and prose on the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Saturday, January 20, 2007

Blog Overview

Friday, January 19, 2007

The Baskets of Baghdad

Brimmed baskets, balanced carefully

Above black abas flowing free,

Glide through thick crowds, responsibly.

Here are some curving fish

Swimming on ice in a dish;

And here some peppers, red and green,

Mixed with peeled onions, white and clean;

Rose pomegranates and yellow pears

Piled high like beaded palace stairs;

Some frightened chickens, staring down

To make a feathered jewel-eyed crown.

Melons striped and shimmering grapes,

Heaps of eggs and mounds of dates,

Leban, biscuits, nuts, and bread

All ride in state upon the head.

Brimming baskets lifted high

Raise rainbowed bridges in the sky.

Sleeping Child

Brown and beautiful

in her blue dress,

The child slept

beneath the shop shelves

Where her father kept his needlework,

Brass wares and hand-carved elephants.

White-robed, he sat beside her,

Sewing slowly, wrinkle-eyed,

Seeming to stitch contentment

into their obscure lives.

It was the quiet time.

No shoppers crowded through

the foot-scarred streets;

No motion of the sun betrayed eternity.

And then I chanced upon

this Joseph and his child,

This mortal, deathless pair,

Sewing the soft, sweet threads

of swift humanity;

Sleeping the guileless sleep

of blue-gowned childhood,

Brown and beautiful.

Once in Louisiana

I walked at evening on a gravel road

That stretched forever toward

the sinking sun.

Not a tree, not a bird,

Nor any colored stone

do I remember now —

But only that I was alone

At sundown on an empty road.

Today the ageless sun swings down

toward Abu Ghraib,

An old Iraqi town;

And on this roadway to the west,

I wonder where the years have gone,

And if I still am walking on

Louisiana stone.

The Lost List

The Gulf War of 1991

An early morning rain, fresh and inviting, was falling

softly, almost secretly, in Victoria. It was the dormant,

damp, often mild season when long dead leaves of

summer creep forth from hidden places like

substantial ghosts to lie in the rain. The spring-like air

curled beneath Elizabeth Simms' umbrella and brushed

her face; but she walked numbly through the soft thin

silk of the rain, feeling apprehensive and helpless.

Her mind was in Baghdad — a city sacred to her

through long years -- and this was the day, almost

certainly, that it would be bombed. During a school

year long ago, brown, beautiful faces had watched her

almost worshipfully, listening to her talk about

Shakespeare and Keats and Hardy. Now she knew the

streets of Baghdad were filled with panic and fear, not

with noisy cars and creaking carts, occasional camels,

flocks of sheep, busy voices and hurrying feet.

With downcast eyes, she walked slowly, solemnly

along the deserted avenue toward the Blethering Tea

Shop a few blocks from her cottage. A ragged piece of

paper, tangled in a cluster of leaves along the curb,

caught her eye. Her first inclination was to pick it up,

not so much out of curiosity as from a vague desire to

remove a kind of intruder or blemish from the world

of the rain. She dismissed the impulse and went on to

the tea shop where she often began her mornings.

Glaring headlines in newspapers in the foyer

heightened her distress: "Americans Poised to Bomb

Iraq; Desert Storm to Be Unleashed." She felt vacant

and chilled, fearing to visualize what was going to

happen on the soil and to the people she loved. Her

days in Baghdad had been exotic; exhilarating, and

magical — days so precious they could never be lost.

Every day of the school year she had traveled from

Mamoun on the outskirts of Baghdad across town to

Waziria to teach at the university. Looking down from

the upper deck of a red British-style bus, she delighted

in the colourful chaos of carters and cars, countless

kiosks and crowds, sidewalk vendors, and headborne

baskets of fish, leban and fruit. She was at home in

the city, "happy as the day was long."

Whenever she missed her bus and crowded into a taxi,

there were deferential smiles — always attempts to

exchange some words beyond simple greetings and

goodbyes.

Whether traveling by bus or taxi, Elizabeth had to

transfer at the Martyrs Square, one of the busiest

interchanges in Baghdad. Buses, taxis and commuters

congregated and departed in continuous waves, filling

the very air with the feeling of imperative destinations.

Elizabeth was at one with the crowd, anxiously

waiting for a bus, or flagging a taxi.

The shrill calls of vendors punctuated the heavy chug

and exhaust of the engines. On an island in the middle

of the square, soapbox orators directed unheeded

messages to the bustling parade of passers-by.

Elizabeth crossed the Tigris every school day over the

Martyrs Bridge. When she returned home at evening,

she sometimes took another route, wishing to look at

the city from a different rainbowed bridge. Crossing

the placid river, she was immortal, a wonder-filled

child, surrounded by Eden alive and ancient, riding

back and forth over the waters of the beginning

oblivious to time's swift passing and the sovereign

might of melancholy.

Seated at tea, she looked out intently at the rainwashed

street, trying to dismiss her fears. Her

thoughts turned back to the water-soaked scrap of

paper she had seen. A strange restlessness came with

the recollection. She felt oddly possessed by the notion

that a list of some extraordinary significance was

scribbled on the paper and that it had something to

do with her.

She chided herself. She was overtired. Her night had

been nearly sleepless, her worries about the war

constant; so her mind had drifted into irrational

assumptions over a discarded or lost piece of paper.

Still, she was unable to entirely suppress conjectures

about it. She wondered what, if anything, was written

upon it and who might have lost it.

She recalled Granny Weatherall in K.A. Porter's story

saying, "It's bitter to lose things!" and nodded in

decided agreement. Then she smiled inwardly for

allowing the supposed list to taunt and tease her as if

she herself had actually misplaced something.

But the matter was not closed. On the way back to

her cottage, Elizabeth saw an elderly man near the

spot where she had seen the list. She felt certain that

she saw him bend down and pick it up although she

was quite some distance away and could not be

absolutely certain. The man disappeared from her

view, turning the corner into Clive Street. When she

arrived with a twinge of anxiety at the spot where she

had seen the paper, it had, like the man, disappeared.

She felt irritated — cheated! The man had somehow

impinged upon or even trespassed upon her territory.

Then she caught herself a second time and actually

laughed aloud at herself in the empty street. Hadn't

she, after all, nearly picked up the piece of paper?

Why begrudge anyone who had felt the same

inclination? Perhaps a list of some kind belonged to

him. What difference could it possibly make if it

didn't?

At home, the list evaporated from her thoughts. She

was drawn to the continuous dispatches of impending

war — the uncompromising resolution of the United

States to "storm" the desert and bomb Baghdad. She

shuddered at the specious rhetoric of war — civilians

would be in relatively small danger; no harm was

meant to the Iraqi people. When she heard reports

that installations to the west of Baghdad were

considered to be prime targets, her fears became even

more intense and vivid.

She had lived with her husband in Mamoun, a suburb

west of town. The district was a mélange of

moderately large brick houses, tin-walled shops, and

open areas where chickens and sheep wandered about

in brown dust and niggardly vegetation.

The house that Elizabeth and her husband rented was

a tall brick structure with a walled-in garden, located

within sight of the highway leading to the west — to

the College of Agriculture at Abu Graib; to the vast

dust-blown desert and the black rocks of Jordan; to

Amman and Jerusalem and Damascus.

Elizabeth had no idea what was meant by military

installations; but she visualized the whole district

between Mamoun and Abu Graib as having been

expanded into a target area for U.S. bombers.

She was torn by an irrational anxiety for the house

she had lived in and for the agricultural school where

her husband had taught. Most of all, she feared for her

neighbors who were engraved unchanged in her

memory — the rotund, cheerful shopkeeper Jassim,

still trying to teach her Arabic as he learned English;

the lad Ayad from next door, bringing gifts almost

every day of delicious flat bread, along with fly-ridden

yogurt; the kerosene man with his donkey-drawn

wagon, surrounded by children; familiar bus and taxi

drivers slowing down forever where she waited every

morning on her way to work. It was as if the

threatened war caught and sealed her back in time,

even as she had been caught up in a timeless

existence while in Baghdad. Every trip through the

city was exciting and eternal; every day in the

classroom green and golden.

Nonetheless, she recalled her first days in the

classroom with a mixture of amusement and pain. The

variety she had seen in the Baghdad streets absolutely

vanished. She walked into rooms filled with identical

faces and forms. She could distinguish the sexes, of

course; but in every classroom she found herself in the

midst of look-alikes!

Not only identical in features, but in dress: all of the

males in the same suits and ties; all of the females

wearing the same jewelry and identical black miniskirts.

Her mind became a blur before a dark-eyed

wave of brown faces; she herself stood shuddering on

a distant shore — honey-blonde and self-consciously

white.

Not being able to differentiate frightened and

embarrassed her, and the same traumatic failure was

repeated in all of her early meetings. Some

consolation came from her husband Allen who, in his

first classes, experienced the same confusion and fear.

Allen compared his dilemma with once having viewed

a gallery of fascinating paintings by schizophrenics —

the same intricate and complicated images reproduced

exactingly over and over again.

Later, the two could recall those early days and laugh

comfortably together, having quickly learned the

names of all of their students. Shortly, it became a

common practice to go with them on week-end

excursions. They traveled to the Golden Mosque of

Samarra, to the ruins of Babylon, to the Holy Cities of

the South, to small villages on the banks of the Tigris

and Euphrates.

At picnic time, a banquet of food miraculously

appeared, placed upon tablecloths spread upon the

ground — lamb and chicken, fruits and vegetables, flat

bread and cheese, dolma and dates. There was singing

and dancing and games, and always amusing

spontaneous lessons in language.

In the bus everyone ate "hub" — pumpkin seeds,

sunflower seeds, and pistachios. The husks were

tossed, as if by communal obligation, on the floor.

Singing in the bus was continuous, mostly in Arabic,

but intermixed with snatches of English.

Echoes and visions and faces congealed and focused

and floated through Elizabeth's mind. She had had

some correspondence but seen no one from Baghdad

through the years. Always there was the intention of

revisiting Iraq, but time and circumstances intervened.

During and after the Iran-Iraq war, all contacts were

lost.

Elizabeth and Allen had managed to travel all the way

to Samarkand, but that was during the conflict

between Iran and Iraq. In Samarkand, the mosques

and markets, the dress and the language reminded

them of Iraq, and they longed to go to Baghdad. Even

after Allen's death, Elizabeth longed from time to time

to revisit Baghdad. Even now, at the moment of

impending conflict, she longed to be in her adopted

city. And her mind was there.

Throughout the day, she kept turning the television

off and on wishing to shut out the inevitable which

she knew she must face. She busied herself halfheartedly

at chores, tried to read, called her friend

Agnes next door several times.

The rain continued to fall all day, but in the late hours

of the afternoon became quite heavy. She looked out

at the gray skies and unrelenting rain as at an infinite

expanse of inexplicable despair.

Agnes came over soon after Elizabeth's third phone

call, sensing the mounting distress in her voice which

was characteristically calm and resonant. Tea and

biscuits were set while the two repeated snatches of

the concerned conversation exchanged on the phone.

Elizabeth sipped her tea, but was soon up pacing. She

carried her serviette and began twisting it in her

hands.

Agnes began to worry. She suggested that Elizabeth

take a sedative. Elizabeth was emphatic: she would

not! The culprits and the brainwashed needed

sedatives, not she! Agnes had never heard Elizabeth

speak in such a fashion. She suggested that they turn

the TV off and take a walk in the rain.

Elizabeth did not want to walk in the rain. She had

been walking in the rain all day! She had walked in

the rain all her life!

Agnes knew very little about the symptoms of

nervous exhaustion but felt Elizabeth was on the

verge. She began to be greatly troubled, not knowing

how to manage Elizabeth's comments and behaviour.

Suddenly, Elizabeth was kneeling in front of the

television screen speaking derisively into the face of

the newscaster. "Oh yes, of course, of course, they'll

have to bomb the bridges! All of them, of course! The

Northgate Bridge and the Second Bridge and Martyrs

Bridge and the Southgate Bridge and the New Bridge

— all of them! And they musn't forget to destroy my

house and Bus 21; and to mutilate my sheep and

chickens and camels and mosques and Mona and

Farej, Abbas and Zahia, Majid and Nawal, Makia and

Mohammed!" Her face was buried in her hands in a

flood of hysterical tears. Agnes knelt beside her,

weeping, trying to console her, not knowing what to

say.

"Elizabeth! Elizabeth! It hasn't happened. Perhaps it

won't happen. Please, come sit down. I think we

should call Dr. Miller."

Elizabeth struggled to her feet, dizzy and nauseated.

Agnes helped her to the divan.

No, Elizabeth didn't want Dr. Miller to be called. She

wanted the television turned off. She would get hold

of herself; she just needed a little rest. She'd stretch

out on the divan, and after awhile, if she didn't feel

better, they would call Dr. Miller.

Elizabeth was in her late sixties and had always been

remarkably energetic and healthy; yet, the strain of

the last several days had been constant and, finally,

unbearable. It was as if her whole life were being

undermined; as if she were being catapulted back into

her youth and the joys she had cherished and

nourished were about to be cruelly destroyed.

She turned to stone on the sofa, absolutely immobile;

so much so that Agnes could scarcely see her

breathing.

She breathed, or scarcely breathed, in Baghdad. She

stood immobile, frozen, sculptured by the roadway,

moveless as death, waiting for the bus from Abu

Graib. Along the road before her, transfixed, wooden

as toys, stretched a convoy of tanks and soldiercrammed

trucks. No one, nothing stirred. The wind

was whisperless, the desert without dust. No veil, black

robe, or palm leaf fluttered. No carter, camel, boot, or

pebble moved. All currents in the Tigris ceased; the

sun was captured in its course, all time suspended.

White flocks of storks above the North Gate Mosque

were stilled in flight like painted ghosts upon the

dome of heaven. The universe was carved in wax and

stone, a single monument, motionless, fervorless,

soundless, sealed in a timeless syncope. All movement

was arrested and waited as in agony for some

momentous signal to begin.

She knew if she should raise her hand the dreadful

armistice with time would cease; the bus would come

from Abu Graib, the convoy move, and every grain of

sand be witness to untold calamity.

She would not move! She would not let one bird song

rise up from the ground, the winds to breathe, the

Tigris to start flowing. She would prevent the advent

of disaster by standing by the roadway fixed forever!

She would not turn back toward her house to wave

goodbye or ever board the bus again to cross the city

to Waziria.

A tear coursed down her cheek and set the sun and

moon in motion.

A whirlwind swallowed up the moments of stilled

time! A great collision rocked the Martyrs Bridge and

earthquaked through the world's foundations. The

severed heads of screaming storks rained blood into

the trembling river.

She ran in terror through the streets, rending her

garments, crawling, raving, looking wildly for herself

among the ruins; rushing from black-robed woman to

black-robed woman beseeching everyone to give her

back her child.

"Allah be praised, Allah be praised,” echoed hollowly

from headborne load to headborne load, from molten

skies, from hidden passageways, from every stone,

from widening fissures in the pavement.

She rushed down avenues of pain, frenzied, tormented,

undone by the cruel ways of Allah, shouting,

imploring, "Elizabeth! Elizabeth!"

The crater that devoured her was a whirling funnel —

a vast, deep hourglass filling swiftly, inexorably with

sand. Her body floated, swirled, and eddied among

dismembered dolls, demented birds, and shards of

fallen monuments.

Suddenly, the buoyant sands released her and she fell

— headlong — through a narrow crevasse into the

nether spaces of the universe. Through the dens of

Nightmare and her Ninefold, age after age, eon after

eon, she fell the length of time into the smoke-filled,

blackened smithy of primeval pain — stretched out

upon an ancient anvil, wrapped in chains.

Agnes saw her stir and was relieved to see some

movement; but Elizabeth was lying, in solitary vigil,

upon a block of concrete beneath the broken girders

of the Martyrs Bridge. The clamour and terror of

armour and sirens had ceased; the feet of the living

had drifted away through the twilight to vague

destinations. Circled in sackcloth, a stoic moon had

climbed the sky, whitening the great shattered bones

of the bridge, broken and strewn in the river.

Elizabeth heard the waters washing about the

desecrated fragments of the fallen bridge. The waters

were crimson. The bodies of the slain floated and

swirled in the debris of the bridge. No faces were

familiar. In the moonlight and crimson no features

were distinguishable, none different. All were brown

leaves come secretly forth to lie in the Tigris at

evening.

Elizabeth knew that the thin green-covered class book,

in which she had written their names, floated

somewhere among them; but it had been carried by

merciless currents beyond the reach of her vision.

Other Poems Included in "The Baskets of Baghdad"

IRAQ

Where Once My Father Walked

Babylon

The Baskets of Baghdad

Man and Stones

The Carter

Shuhada Square Twin Reality

Woman and Child

Day’s Shadow

The Shovelers

Ahl as-Sarifa

Moslem in the Fields

TrinityCircling Birds

The Golden Mosque

The Long Miles

Hospitality

Impression of Evening

Lovers’ Ghosts

Woman of the Basrah Streets

No Tales of Arcady

Alms

A Wall in Hilla

Still Does He Sing

Day of Dust

Latent Images

By Babylon’s Shores

Tooth Pulling

Coppersmith

Black Rocks of Jordan

Bedouin Love Song

Flight Into Egypt

And There Were Shepherds

The Carpenter’s Son

Sleeping Child

Mother and Children

Dome of the Rock

Harvest

Summer’s End

Sorrow

Quiltmaker

Hattaba*

The Winds of Winter

Pilgrims

The Coves of Memory

Last Flight to Eden

Retrospect

Night’s Shadow

Departure

The Lost List

Voices

Intaglio

Kindergarten to Iraq

The Circle

Sarmad the Jew

Puerto Iguazu Madonna

Purchasing "The Baskets of Baghdad" in Print

List of Stanley Freiberg's Works

Plays

Jahanara: Daughter of the Taj Mahal (1999)

Sverre, King of Norway (1999)

Blake and Beethoven in the Tempest (1997)

Mad Blake at Felpham (1987)

Bush, Blake & Job in the Garden of Eden (2005)

Poetry

The Baskets of Baghdad - reprinted (with additions) (2006)

The Dignity of Dust: Poems from the Four Directions (1997)

The Hidden City: A Poem of Peru (1988)

The Caplin-Crowded Seas: Poems of Newfoundland (1975)

Plumes of the Serpent: Poems of Mexico (1973)

The Baskets of Baghdad: Poems of the Middle East (1967)

Short Stories

Nightmare Tales: Ten Inter-related Stories of Kings County, Nova Scotia (1980)

On Gravel Roads: Eight Inter-related Stories of rural Ontario (2004)

Historical Dramas

Black Madonna of the Deluge (2000)

The Two False Dmitris: Russia in the 'Time of Trouble'

Anaho of the Southstars: a Novel of Nevada (2003)

On Gravel Roads: Tales of Early Ontario

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Biography

Retired from the University of Calgary department of English in 1979, he has taught at universities in the United States, Canada and Baghdad, Iraq.

His published works are recorded in Who's Who in International Poetry (Cambridge, England) and Who's Who in Canadian Literature (Toronto). His critical opinions and personal comments on art are cited in Contemporary Authors (Detroit).